Highlighted Stories

A Generation Left Waiting: Gaps in SDG progress for children

In 2015, world leaders agreed on 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) to end poverty, tackle inequality and climate change, and create a better future for everyone. A new analysis by Save the Children, using a machine learning model to better understand the link between public policies and outcomes, paints a sobering picture. Despite progress in some areas, significant gaps remain for children worldwide – and many are unlikely to be met within the lifetime of today’s children, or even the next generation. The UN World Social Summit this week in Doha offers a pivotal opportunity for global leaders to recommit to sustainable development, eradicating poverty, and creating equitable opportunities for all.

Progress and persistent challenges in reaching the SDGs for children

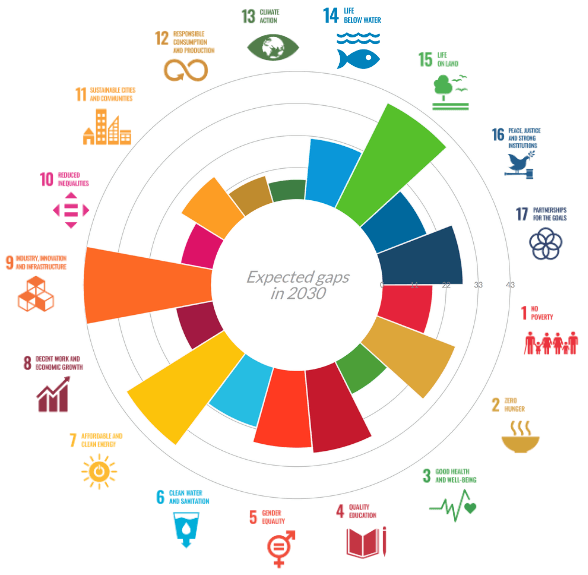

Our analysis covers 90 child-relevant indicators across all 17 SDGs (many of which are available in the Child Atlas), and takes into account the important interlinkages between different policy areas. Some of the largest gaps globally appear in hunger and nutrition (SDG 2), education (SDG 4), affordable and clean energy (SDG 7), industry, innovation and infrastructure (SDG 9), and life on land (SDG 15). These gaps, however, vary significantly between income groups and regions. The widest gaps are found in Sub-Saharan Africa, followed by South Asia and the Middle East and North Africa – but the SDGs remain unfulfilled everywhere, including in high-income countries.

Beneath these gaps lie the real lives and prosperity of children worldwide. Under current policy priorities – and without substantial additional investments in children and families – around 750 million children are projected to still be living in multidimensional child poverty across low- and middle-income countries in 2030. 3.4 million children under 5 are expected to die before their fifth birthday and as many as 224 million children might be out-of-school by the end of the decade – despite the SDGs’ promises to end preventable child deaths and ensure that all girls and boys complete free, equitable and quality primary and secondary education.

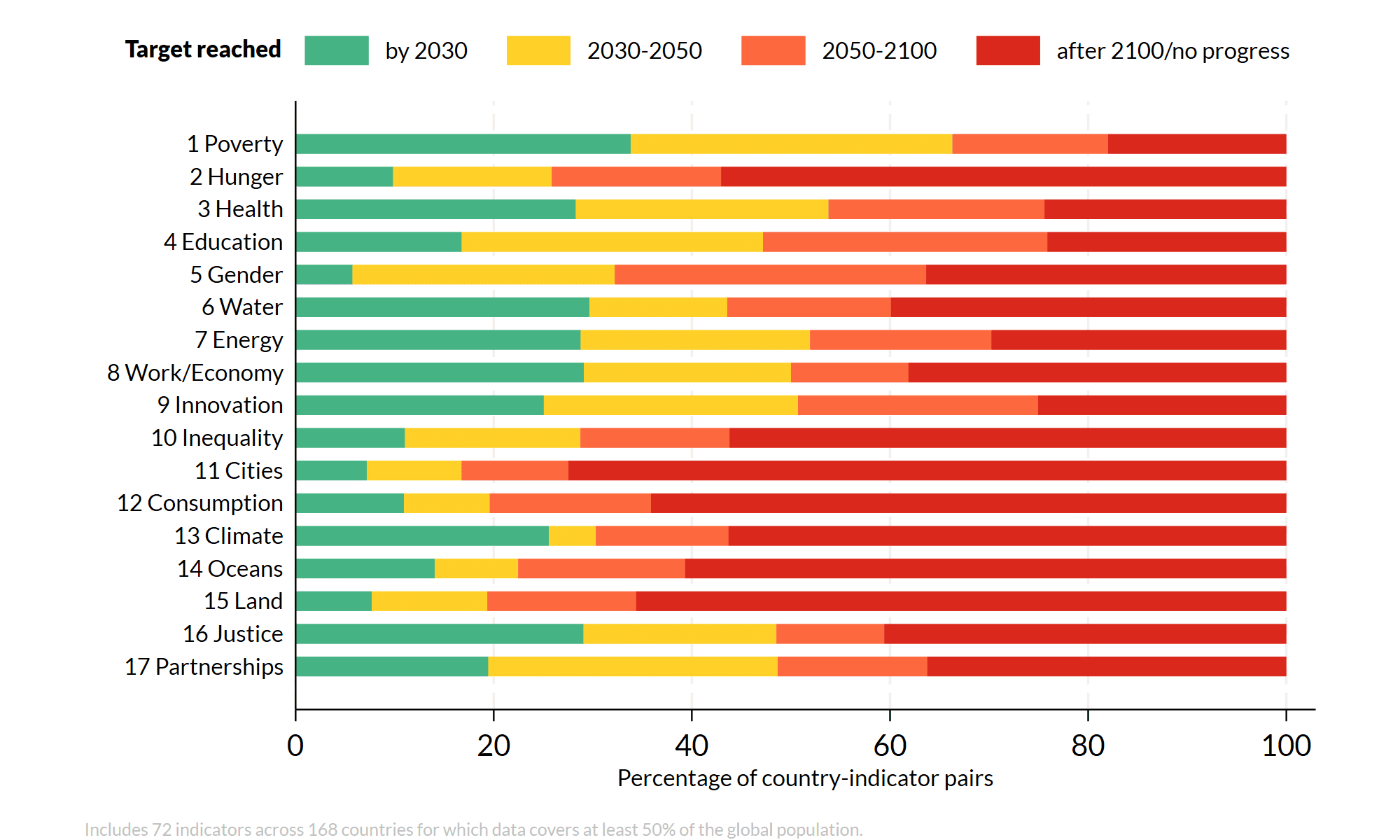

Falling behind: Most countries won’t reach the SDGs in time

Progress matters as much as the size of the gap. Even large gaps can close quickly if progress is rapid, while smaller ones may persist for decades if progress is slow or indicators are regressing. Our model – covering 170 country-specific analyses and up to 90 individual indicators – estimates how long it will take, based on current trends, to reach the SDG targets. The findings are stark: only 20% of country-indicator pairs are expected to reach their targets by 2030. Globally, more than half are unlikely to reach the goals by 2050. And 607 million children live in countries where most indicators are regressing or will not meet their targets until 2080 or later – half a century after the 2030 deadline. Progress is particularly slow for hunger and nutrition, gender equality, inequalities, sustainable cities, and many planet-related goals such as life on land and below water.

A foundation to better understand public policies for children

Failing to deliver for children now undermines the global community’s vision for a sustainable, peaceful and prosperous future set out under the 2030 Agenda. This analysis offers new insights into the world’s far-too-slow progress towards the SDGs under current policy trajectories (and complements other more traditional efforts, like the ones by UNICEF in 2023 and those presented in the Child Atlas’ SDG page). It also provides a foundation to better understand how public finance decisions affect children – and how to identify public policies that deliver the greatest impact for them.

This is the first Save the Children analysis using the Policy Priority Inference (PPI) framework, developed at the Alan Turing Institute. The PPI is a computational model that integrates large amounts of empirical data with a robust theoretical framework, capturing the workings of complex systems and the realities of political economy. Check out the briefing (and full methodological note) for further information on the methodology.

Related stories:

Related stories

How a Soap Opera Helped to Reduce Child Marriage

Child protection (CP)

Child protection (CP)

2025-12-09

Does Insurance Benefit Child Health? Lessons from 38 Countries

Health (HL)

2025-11-19