Highlighted Stories

Does Insurance Benefit Child Health? Lessons from 38 Countries

Health insurance can play a crucial role to protect from high out-of-pocket costs that families and children often face when they need to access health services in many low-and middle-income countries. But does insurance actually help to improve outcomes for children? As part of my internship at Save the Children through UCL’s Social Data Institute Internship Scheme, I analysed Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey (MICS) data from 2017-2023, covering approximately 340,000 children under five across 38 low- and middle-income countries. This blog post, summarises some key insights about the association between insurance and child health outcomes.

The findings reveal a consistent pattern: insured children show better health outcomes than uninsured children across most countries. But before celebrating this as evidence for insurance expansion, we need to understand what these associations actually tell us—and more importantly, what they don’t.

What was Measured

I examined three health indicators: Stunting reflects chronic malnutrition during critical early years. DPT3 vaccination measures routine preventive healthcare access. Care-seeking for diarrhoea reveals how families respond to acute illness. Together, these indicators capture distinct dimensions of child health and healthcare access.

Focusing on Robust Comparisons: The Statistics Explained

Our analysis covered 38 countries, but for this blog, I focused on those with large enough sample sizes to yield reliable results—specifically, where we observed sufficient numbers of insured and uninsured children. I then calculated odds ratios for these countries. An odds ratio indicates how much more or less likely insured children are to experience a certain outcome: if the odds ratio is above 1, it means insured children are more likely to be vaccinated or seek treatment; if it's below 1, they're less likely; and if it's exactly 1, there’s no significant difference between the two groups.

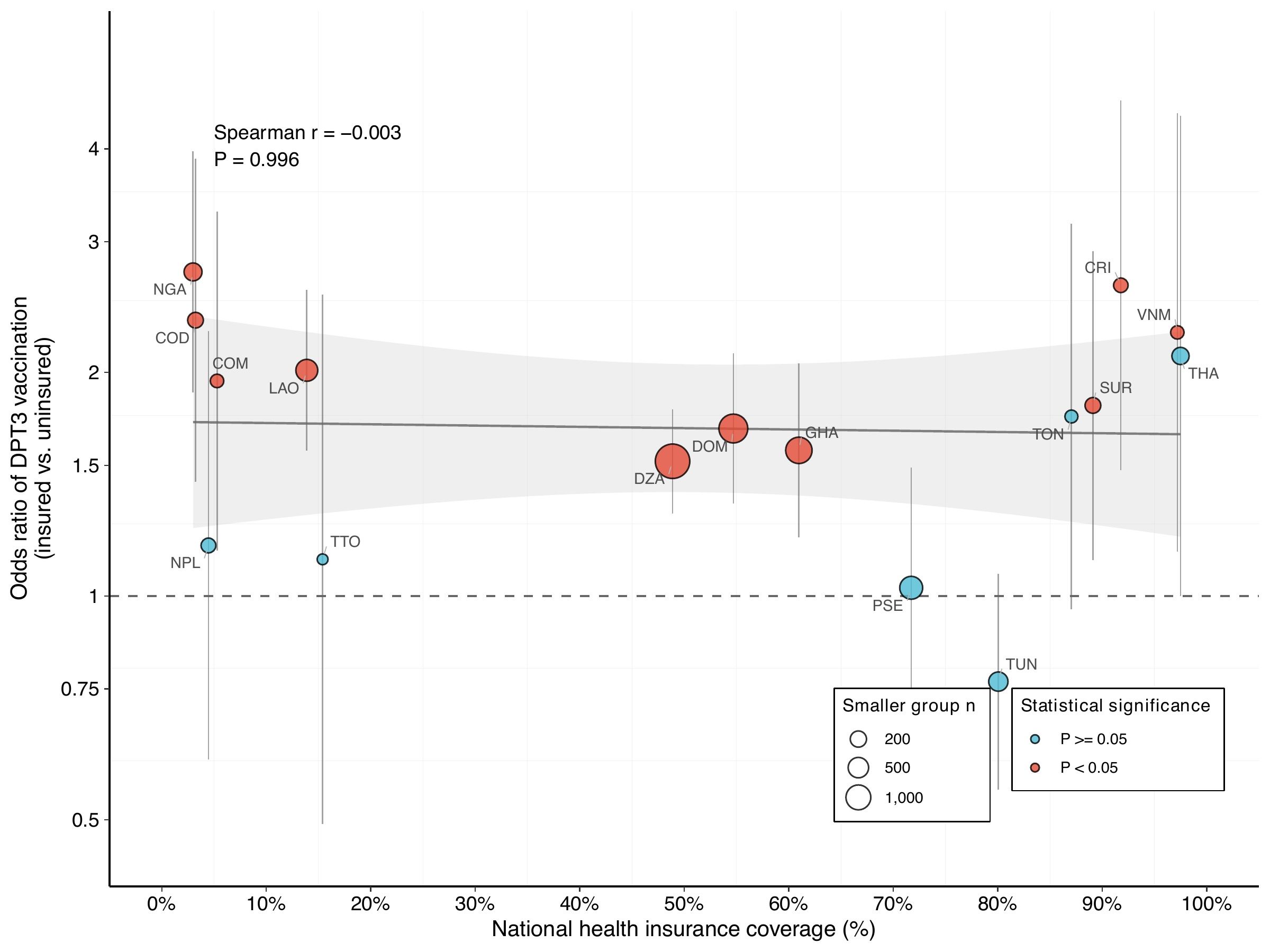

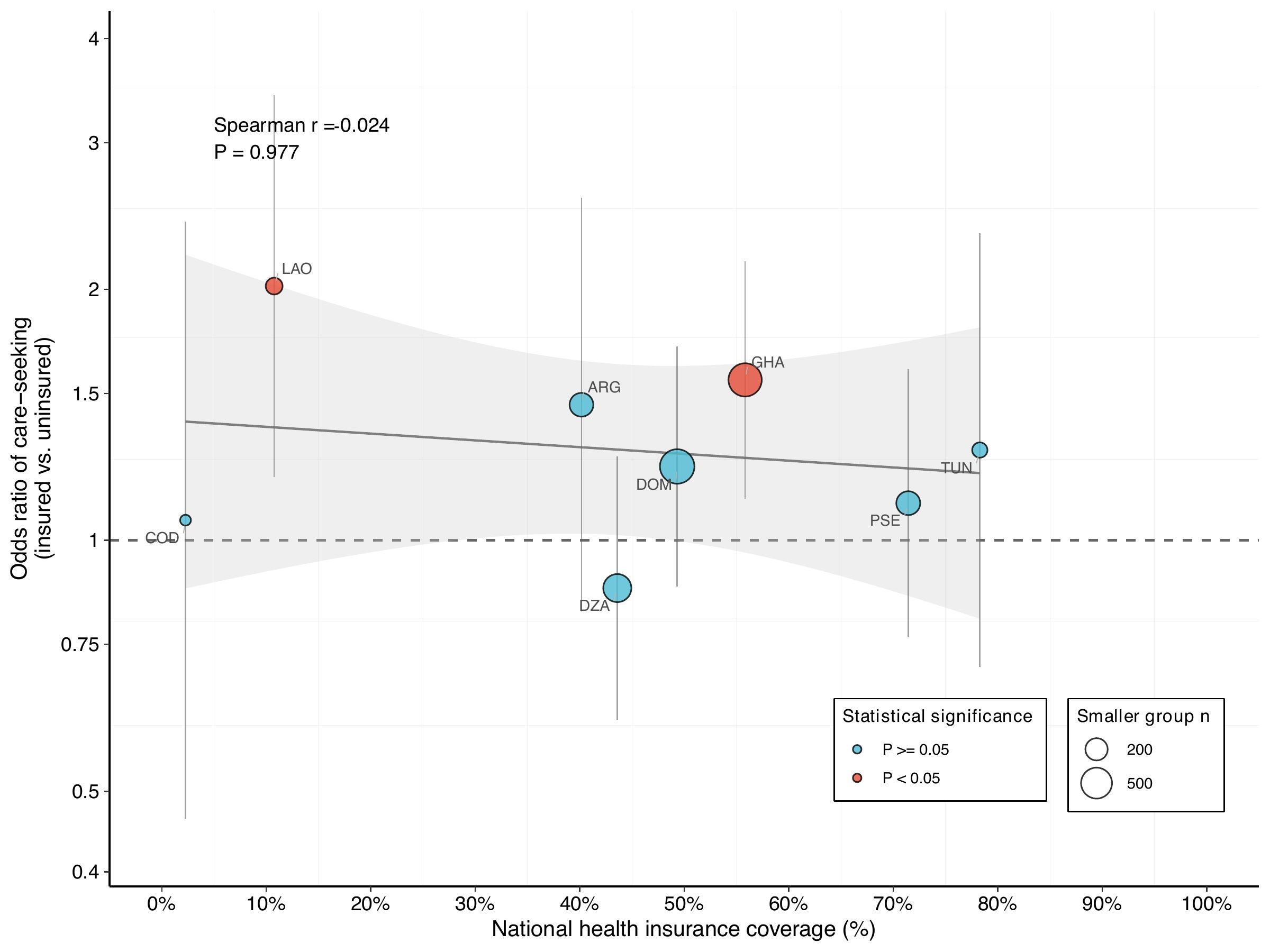

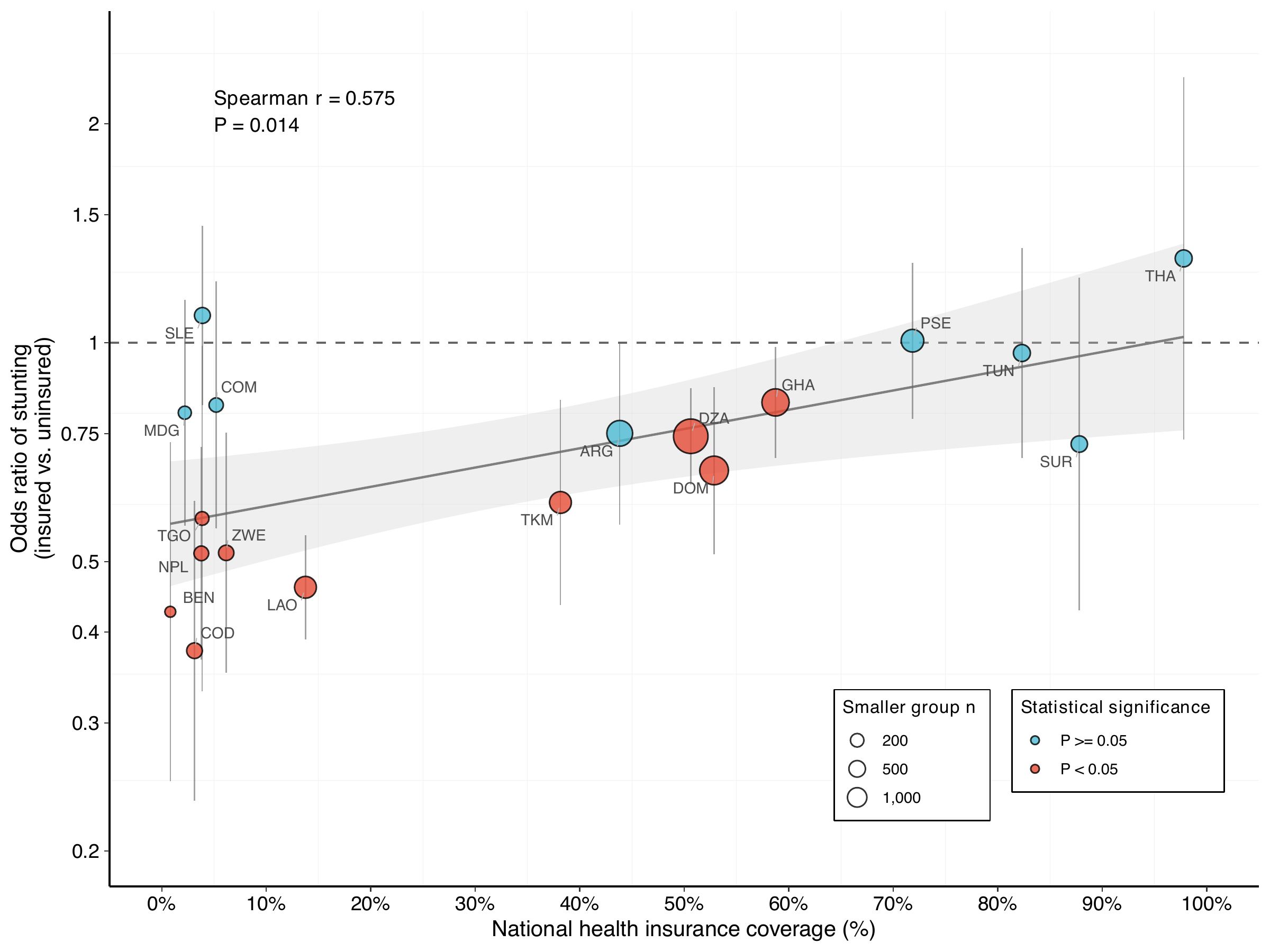

These odds ratios are shown on the vertical axes in the graphs below. The horizontal axes show the insurance coverage: moving further to the right means more children have insurance. Each dot corresponds to a country, with larger dots indicating bigger sample sizes and, therefore, stronger data reliability. Red dots highlight associations that are statistically significant (meaning we can be confident the results aren’t just due to random chance), whereas blue dots indicate associations that didn’t reach statistical significance.

DPT3 Vaccination: Predominantly Positive Associations

For vaccination, most countries show positive associations—insured children are more likely to be fully vaccinated. In low-coverage countries (under 15%) like Nigeria (2.9%), DRC (3.1%), and Laos (13.7%), insured children are roughly twice as likely to be vaccinated. At moderate coverage (40-60%), Algeria, Dominican Republic, and Ghana show more modest positive associations. The high-coverage picture (above 80%) is mixed: Costa Rica and Vietnam show strong associations, while Thailand (97.8%) shows essentially none despite large sample sizes—suggesting the relationship between coverage expansion and vaccination isn’t straightforward. Country-specific factors like who remains uninsured and how health systems function matter as much as coverage level.

Care-Seeking for Diarrhoea: Weaker Patterns

Diarrhoea care-seeking data are limited to children who had diarrhoea in the two weeks before the survey, resulting in a smaller sample. Only Laos and Ghana show a clear positive link, with insured families being twice as likely to seek care. Most countries show little association, indicating the effect is weaker than for vaccination. This may be because acute illness prompts care regardless of insurance, whereas insurance has more influence on routine services like vaccination.

Stunting: Increased coverage reduces insurance’s positive impact

For stunting, the majority of countries demonstrate protective associations, indicating that insured children have a reduced risk of chronic malnutrition. The pattern across different levels of insurance coverage is striking: at low coverage (under 10%), insured children in DRC, Laos, and Nepal are half as likely to be stunted. At moderate coverage (20-60%), these associations weaken. At high coverage (above 70%), insurance has minimal impact.

Unlike the other outcomes, stunting shows a statistically significant relationship between coverage level and association strength; as coverage increases, the protective association weakens. This likely reflects stunting’s cumulative nature: This pattern likely reflects the cumulative nature of stunting: it develops over extended periods due to ongoing nutritional deprivation, inadequate sanitation, and recurrent infections. In countries with low insurance coverage, those with insurance are typically from socioeconomically advantaged backgrounds with superior nutrition and living conditions, independent of their insurance status. The large differences we observe may reflect who has insurance as much as what insurance does. This suggests we need to be cautious when interpreting these associations as evidence of causality.

A research report with the complete analysis is available here – and you can also interact with the data in this visualisation.

A country perspective

Ghana’s National Health Insurance Scheme (NHIS), established in 2003, provides a compelling example of how insurance can improve child health outcomes. As I showed above, insured children in Ghana are more likely to receive routine vaccinations, seek care for diarrhoea, and have lower stunting rates. There are several factors that help explain why Ghana stands out compared with other countries: first, NHIS coverage is relatively high and the scheme is well-integrated with public health services, ensuring children can access care more consistently. Second, the scheme benefits from a stronger health system and better infrastructure compared to other low-income countries. Third, Ghana’s system effectively links enrolled families – particularly in urban and moderately advantaged households - to preventive and curative services. As a result, Ghana – despite ongoing equity issues - achieves far greater benefits from insurance than many other countries, where low coverage, widespread inequities, and an under-resourced health system mean children often cannot reliably access quality care even if they are insured.

A crucial caveat – and what this means

This analysis provides us with some important insights, particularly regarding the relationship between health insurance coverage and health outcomes. Nevertheless, it is important to note that these patterns should not be interpreted as causal evidence that insurance improves health outcomes. The primary issue is selection bias, wherein children with insurance often differ systematically from those without. Both insurance coverage and health outcomes are closely associated with factors such as wealth, education, and urban residence. Thus, when insured children appear to experience better outcomes, this reflects not only the potential effects of insurance but also the characteristics of those who obtain it. This challenge is most pronounced in settings where insurance coverage is limited and primarily accessed by more advantaged groups.

So what does this mean?

The evidence suggests that both genuine insurance effects and selection bias are present. The statistically significant association between coverage level and stunting, but not with vaccination or diarrhoea, indicates that different health outcomes may respond differently to insurance coverage. Long-term nutritional outcomes, in particular, appear especially susceptible to confounding factors. To generate robust causal evidence, researchers should employ more sophisticated methodologies, such as leveraging natural experiments or conducting randomised evaluations.

That said, these findings shouldn’t discourage expansion of coverage. Financial protection matters regardless of its immediate health effects, and the positive associations align with hypotheses that reducing financial barriers improves health outcomes, especially for preventive services. But we also find that context matters enormously. Policymakers should expand coverage and rigorously evaluate whether insurance actually improves health in their specific context.

About this analysis: This research was conducted during an internship at Save the Children UK through UCL’s Social Data Institute, analysing MICS data from 2017-2023 covering 38 countries. I am grateful to my supervisor Olivier Fiala, the Save the Children UK team, and the UCL Social Data Institute for their support and guidance. For questions, please reach out to sacha.bechara.23@ucl.ac.uk

Views expressed are the author’s own and don’t reflect positions of Save the Children or UCL.

Related stories:

Related stories

How a Soap Opera Helped to Reduce Child Marriage

Child protection (CP)

Child protection (CP)

2025-12-09

A Generation Left Waiting: Gaps in SDG progress for children

Indicators by SDGs (SD)

2025-11-04